Mississippi Today Headlines GRI and NGI Researchers' Work: When Invasive Plants Attack, a New Tech Tool Can Nip it in the Bud

June 23, 2017

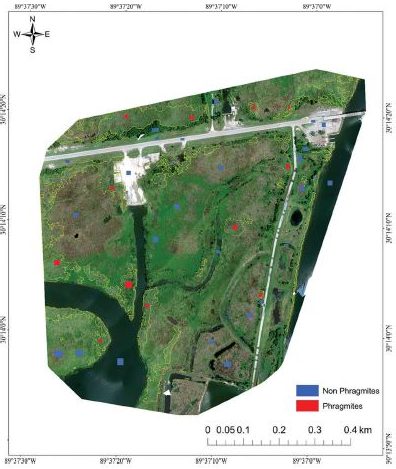

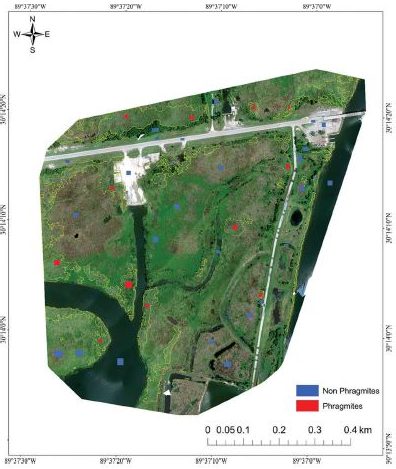

Courtesy of Sathishkumar Samiappan, Gray Turnage, Lee Allen Hathcock and Robert Moorhead.

Red areas show where an invasive grass along the Gulf of Mexico called Phragmites Australis, or common reed grows.

A couple of years ago, a group of Mississippi State University researchers were using new technology to map the Lower Pearl River delta for forecasters when they saw an alien species — of plant, that is.

An invasive plant species called Phragmites Australis, also known as Common Reed, is a tall grass that can be found along coastal areas of the Gulf of Mexico.

This invasive Phragmites is a problematic weed in many states because it forces out native plants in those areas by outcompeting them for resources such as space, sunlight, water and nutrients.

It can also alter wetlands ecosystems and increase the potential for fire. Typically growing to around 16 feet, a full-grown plant can make navigation and visibility difficult for small boats.

Gray Turnage and Sathish Samiappan, who are both research associates at Mississippi State University's Geosystems Research Institute, said they participated in a river mapping project using a special drone and cameras such as a multispectral camera—technology can see what the human eye cannot—attached to collect data.

Turnage said the invasive grass had been growing along the Gulf for many years, but suddenly, using this type of image technology, he could clearly see the areas this plant occupies.

There are Phragmites that are native to North America, but two types of Phragmites are considered invasive.

One type, Haplotype M, can be found along the East Coast and Northern states and is native to Europe. The other type, Haplotype I, is found along the Gulf Coast. Its origin is unknown, but it is suggested to be native of South America or Asia.

Turnage said it would be impossible to verify how the invasive plant found its way to the Gulf Coast. However, invasive species are likely to arrive via travel corridors, like shipping containers, harbors and occasionally airports.

Locating where this invasive species populates is time-consuming and difficult to do manually. The software Turnage and Samiappan used for their drone technology is capable of giving a map of the GPS locations of where the plant is.

"Once you teach it how to identify the target species that you're after, it can find that species with a high degree of accuracy," Turnage said. "In the rest of the imagery, what's collected by that drone, you could hand that over to a resource manager and they can use that for decision-making purposes when they try to manage a specific species."

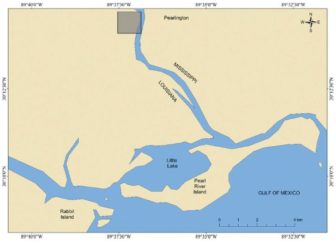

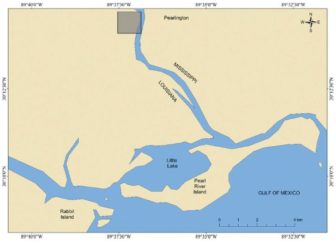

Courtesy of Sathishkumar Samiappan, Gray Turnage, Lee Allen Hathcock & Robert Moorhead.

The land area where the Mississippi State University's Geosystems Research Institute research took place is marked in gray.

Turnage said this camera technology can identify much more than invasive and native plant species. It can monitor crop health and damage signs from animals, among other things. This drone technology could also be used while maintaining forests around the state via prescribed fire.

"It's growing quicker in the agricultural field, crop science and things like that," Turnage said. "It's catching up in the natural resources field, what we call … forests, wetlands and marshes, but still behind other fields of research."

Turnage said many types of items can be mapped as long as a drone can see the item from the sky. This works well for plants not shaded by trees. It can capture images of invasive animals, too, but they are able to move around, so locating those animals on the ground would still be tricky.

Samiappan developed the software used for capturing the imagery during their research. He said satellite data could also produce similar visuals to aid in locating specific plant species.

Getting that detailed data, however, could take as long as two months.

"Satellites don't see the same spot on the ground all the time," Samiappan said. "They revolve around the earth, so there is a time lapse between when you want to collect the imagery and when you can actually get the imagery."

The researchers are further testing this method to make sure it consistently works on a wide variety of problems.

Courtesy of Sathishkumar Samiappan, Gray Turnage, Lee Allen Hathcock and Robert Moorhead.

The drone used during the Mississippi State University's Geosystems Research Institute project on invasive grass along the Gulf of Mexico called Phragmites australis or common reed.

Turnage said the goal is for government agencies, resource managers and farmers to use this method so it can help them do their jobs more efficiently.

This can range from searching for damaged or stressed crops in a large field to take corrective action, to making more-informed decisions about nature preservation around the state.

Should the method meet their standards, Turnage, Samiappan and others would get the message out by giving presentations on their findings and publishing their work in peer-reviewed publications.

"It could be used to increase safety in certain areas," Turnage said. "Humans still have to act on the data. The drones won't do it for you, but it can tell you where action needs to be taken."

Story by Kendra Ablaza

Mississippi Today

Follow her on Twitter: @KendraAblaza.